After reading the book, I found that hypodemic and reception theory both affect the process of moral panic. The hypodemic theory suggests that people receive media messages directly, without filtering or critical reflection (Schirato et al., 2010). This idea helps explain how moral panic can arise and spread quickly. In contrast, reception theory, especially the encoding and decoding model, offers a more nuanced view of how people interpret these messages. This essay explores how hypodermic effects contribute to moral panic and how reception theory provides a deeper understanding of this process.

The hypodemic theory, also known as the magic bullet theory, argues that media messages are injected straight into the passive audience’s minds (Schirato et al., 2010). According to this theory, people accept these messages without questioning them, leading to direct and powerful effects. This can explain how moral panic develops:

1. Conflict highlighted by media: The media singles out a conflict or event, often sensationalized with graphic images and prominent news coverage. This grabs public attention and sets the stage for panic.

2.Framing as a threat: The media frames the event as a threat to societal values, suggesting it could undermine cultural norms and stability.

3. Demonization of perpetrators: The individuals or groups involved are demonized, portrayed as villains responsible for the threat.

4. Expert involvement: Experts such as doctors, psychologists, police, and lawyers are called upon to validate the threat and offer solutions, lending credibility to the media narrative.

5. Public outcry and government intervention: Public fear and outcry force the government or authorities to act, often resulting in new laws or measures to address the threat and restore order.

Reception theory, particularly Stuart Hall’s encoding/decoding model, challenges the hypodemic theory by emphasizing audience agency. According to this model, media messages (encoding) are created with specific meanings, but audiences interpret these messages (decoding) based on their own contexts, leading to different interpretations (Schirato et al., 2010). The model identifies three potential readings of media texts:

1. Dominant-hegemonic reading: The audience fully accepts the intended meaning of the media.

2. Negotiated reading: The audience partly accepts the message but adjusts it based on personal experiences or opinions.

3. Oppositional reading: The audience completely rejects the intended message and interprets it in a contrary way.

Case Study: The 1980s “Satanic Panic”

The “Satanic Panic” of the 1980s is a clear example of how hypodermic effects and reception theory interact in the context of moral panic. Media reports during this time extensively covered alleged cases of satanic ritual abuse, presenting them as a widespread and dangerous threat to children and societal values (Roydons, 2022):

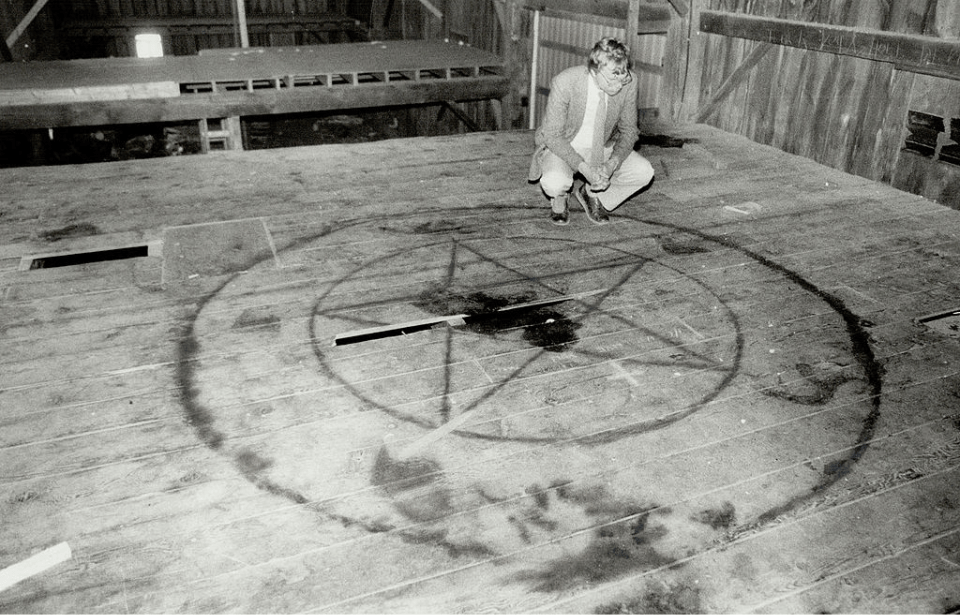

1. Conflict highlighted by media: The media sensationalized stories of satanic rituals, often with graphic and disturbing images, capturing public attention and igniting fear. In April 1989, The Munice Evening Press reported on a incident at a church involving a pentagram, a drawing of the devil, and a one-legged baby doll with a red substance on it. Such stories, often accompanied by graphic imagery, caught public attention and fueled fear.

2. Framing as a threat: These events were framed as a significant threat to societal values, suggesting that satanic cults were infiltrating communities and endangering children. For example, a Utah newspaper in 1985 asked, “Satanism. Is it just a phase the kids are going through or is it a serious threat?”

3. Demonization of perpetrators: Alleged perpetrators were demonized as evil and malevolent, responsible for heinous acts against innocent victims. This is seen in the case of James Dallas Egbert III, whose disappearance and subsequent death were linked to his involvement in Dungeons & Dragons, a game erroneously associated with satanic practices.

4. Expert involvement: Psychologists, police, and other experts were called upon to validate the threat, often interpreting the panic as a symptom of deeper societal issues, such as child abuse and neglect. For instance, in 1988, a supposed expert in South Carolina warned school counselors about the growing problem of satanism, linking it to animal sacrifice, grave robbing, drug use, and sexual abuse. These experts lent credibility to the media narrative, reinforcing public fear.

5. Public outcry and government Intervention: The resulting public outcry led to governmental investigations, legal actions, and new policies aimed at protecting children and rooting out satanic influences. One notable case was the McMartin preschool trial, where allegations of ritual sexual abuse led to extensive legal proceedings, though all charges were eventually dropped due to lack of evidence.

While the hypodemic theory explains the rapid spread of fear and moral panic, reception theory reveals a more complex picture. Not all audiences accepted the media narrative uncritically.

Some individuals and groups questioned the claims, resulting in negotiated or oppositional readings of the media coverage. These varied responses highlight the importance of considering audience interpretation in understanding media effects.

The hypodemic theory helps explain how media can quickly initiate and sustain moral panic by directly influencing public perceptions and actions. However, reception theory provides a more nuanced view by emphasizing the active role of audiences in interpreting media messages. The 1980s “Satanic Panic” illustrates how media can amplify fears and provoke societal reactions, but also how different audiences engage with media narratives in diverse ways. This combination of theories underscores the need for a nuanced approach to analyzing media influence and its impact on moral panic.

Reference

Roysdon, K. (2022, April 7). How “satanic panic” came to roil the nation during the 1980s.

CrimeReads. https://crimereads.com/satanic-panic-1980s/

Schirato, T., Buettner, A., Jutel, T., & Stahl, G. (2010). Understanding media studies (pp. 92–

109). essay, Oxford University Press.

Leave a comment